Some people call it "fake news." Others use the word "misinformation." Semantics aside, concern over untrue information online has erupted over the past decade. The question of how to stop falsehoods from spreading has led to ideas like teaching people to recognize fake information, providing timely fact checks or even using technology to squash falsehoods.

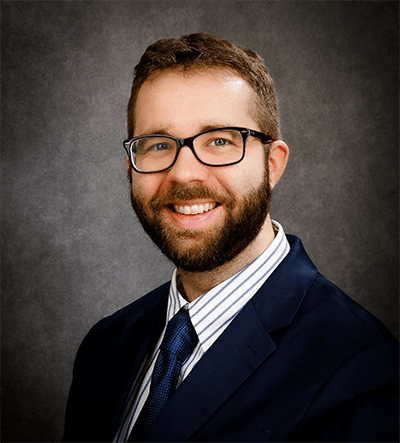

But a new book by a University of South Carolina sociology graduate points out that fighting misinformation is more than a matter of setting the record straight. According to Matthew Facciani, we might need bowling leagues and neighborhood cookouts just as much as fact checks.

"Ultimately, reducing misinformation requires rewiring the structure of our society so we can form different relationships with people and have broader social support," Facciani says. "My book combines various approaches in an effort to reduce misinformation."

In Misguided: Where Misinformation Starts, How It Spreads, and What to Do About It, published by Columbia University Press in July, Facciani draws on years of research to show how our social environments and identities shape what we believe. He demonstrates why rebuilding trust in institutions must be a part of the response.

Facciani originally came to USC to earn a doctorate in neuroscience, but he couldn't ignore his intense curiosity about one question: How do people form their strongest beliefs? That led him to the unusual choice to switch graduate programs.

Facciani spent the rest of graduate school in the Department of Sociology, where he studied political polarization and how the social world shapes political beliefs. His research showed that people's reactions to news headlines depend on whether the headlines support their political party. It also revealed that knowing few people from different political perspectives make a person's ideology more rigid, and that positive connections with those of opposing views could help people become more open-minded.

Facciani was finishing his dissertation in the spring of 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, bringing with it political controversies about social distancing, mask-wearing and school closures.

"I thought, this really applies to what's happening with COVID," he says. Shortly after graduating, he wrote an article for The Conversation explaining why people could be so polarized about the virus. He focused his research on misinformation during postdoctoral fellowships at Vanderbilt University and the University of Notre Dame, ultimately leading to the book.

One of Misguided's central ideas is that misinformation often stems not from ignorance, but from identity.

"We have these identities, these sets of meanings and values that help us navigate our social worlds in a way that makes sense," Facciani says, adding that we tend to act in ways consistent with those identities. "That gives us a self-esteem boost. It gives us a lot of meaning. A lot of it is a very positive thing."

The problem comes when a person's worldview is shaped by narrow, overlapping identities ― for example, if someone's coworkers, family and preferred news source all support one idea, then that idea becomes strongly intertwined with the person's identity, even if the idea is not true.

The solution, then, isn’t just better information, he says. It’s broader networks, more diverse relationships and spaces where people from different walks of life can connect and develop trust. Unfortunately, he says, society offers fewer opportunities than in decades past for people who want to build those broader networks.

“We’ve gotten away from connecting with people on a local level in person. People have become geographically sorted into smaller groups that are more like them," he says. "As we continue to be in our smaller spaces, other people [who disagree] seem scary to us because we only hear about other people when extreme, bad stuff is happening on social media.”

Facciani says there are no quick fixes to these problems, but the solutions would all involve reducing the distance between people and groups. Big institutions like government agencies could increase their outreach and partnerships in communities that feel forgotten in the bureaucracy. Local communities would need to foster more opportunities for people to interact. Individuals could change their routines to get to know more people.

"One of the ways we can protect ourselves against misinformation is not to be so reliant on this narrow set of identities," Facciani says. "The practical examples of this are literally getting hobbies and meeting different types of people, going outside your bubble, so that whenever you see something on the news that challenges one identity, your entire self-worth isn't crumbling because you can rely on different identities. A diverse set of identities offers a broader reservoir of self-esteem, making us more resilient in the face of challenging information."